Although Mesopotamian gods appeared in many forms, they primarily took on an anthropomorphic shape: when the ancient Mesopotamians envisioned the gods, these mostly acted and looked like they did. Gods did not only live in people’s minds, however – they were physically present in their temples in the form of the cult statue.

Gods as statues, statues as gods

Temples served as large-scale households, where the god, his family and his court were given a welcome home with elaborate food offerings, clothing ceremonies and even carefully being woken up in the morning with the appropriate songs. After all, humanity’s raison d’être was to take care of and feed the gods. This idea recurs in a number of Mesopotamian myths and most prominently in the story of Atrahasis. There we find the account of how Mami created the first humans from clay mixed with the blood of a minor deity for the mere purpose of putting them to work:

“Mami made ready to speak and said to the great gods: ‘You ordered me the task and I have completed it! You have slaughtered the god, along with his spirit. I have done away with your heavy forced labor, I have imposed your drudgery on man. You have bestowed corvée work upon humankind.” (Atrahasis I 235-242, Foster 2005)

Cult statues were not mere objects of devotion, however. The ancient Mesopotamians believed that the cult statue was actually the god himself. This is clear from the terminology used, which refers to the cult image as “the god”. Also the way in which the statue was treated, which was reminiscent of how kings were approached, shows how it was revered as a living being. The idea that the statue was the god comes to the fore most obviously at those moments when the god would leave his temple. During festivals, gods would travel to other cities to partake in the festivities there, crossing the land by boat or wagon. At those occasions, the daily service of the god needed to continue and therefore his cultic personnel would accompany him on the trip, providing everything he needed. More dramatic are the moments when a cult statue was “godnapped”. It was a common custom to remove the cult statues from conquered cities, because it meant that the cult could no longer be observed: the gods had left their abode.

The ideological consequences of the absence of the god from his temple cannot be overestimated. When the Assyrian king Sennacherib destroyed the city of Babylon in 689 BCE, for example, he carried off (or destroyed?) the statue of the city’s main god Marduk. For twenty years, Marduk’s cella in his temple Esagila remained empty. Not only could the cult no longer continue, this also meant that the local priesthood, forming the largest part of Babylon’s elite, was left powerless. The deity’s statue was finally returned in the year 668 BCE in a pompous procession that resembled the New Year Festival – an act clearly intended to placate the Babylonian audience. (On a side note: see also the contemptuous reference to the statues of the gods Marduk and Nabû in the Old Testament, Isaiah 46:1-2: “The images that are carried about are burdensome, a burden for the weary”).

The disastrous effects of a deity leaving his temple can also be gleaned from the Epic of Erra. The god Erra, in a cunning plan to wage war, asks Marduk why his “precious image” is so dull and dirty. Marduk answers him that, when he once left his seat to have himself cleaned up, the “regulation of heaven and earth disintegrated”, meaning that the world order reverted into absolute chaos. That is why he would never leave his temple again.

What gods look like

Marduk then goes on to describe how he has hidden the tools necessary for the repair of his statue:

“Where is the wood, flesh of the gods, suitable for the lord of the universe; the sacred tree, splendid stripling, perfect for lordship, whose roots thrust down a hundred leagues through the waters of the vast ocean to the depths of hell, whose crown brushed Anu’s heaven on high? Where is the clear gemstone that I reserved for [broken]?” (Erra I 149-154, Foster 2005)

This fragment is one of the few sources that tell us how cult statues looked. Although there are a number of texts that describe the features of gods, it often remains unclear whether their authors have the cult statue or the god’s general characteristics in mind (as these do not necessarily have to match completely). The same is true for visual representations on seals or reliefs.

Still, there are a number of things we know about the appearance of divine images. The core of the statue was mostly made from wood, which was not a cheap material in Mesopotamia where its natural occurrence was low. On the outside, this wooden core was covered with a “skin” of gold or silver, giving the god a genuine shine. Also precious stones and shells were used to add to the statue’s glowing radiance. The deity was clad in luxurious robes and probably wore wigs. The gods owned multiple outfits for different occasions and were the subject of extensive clothing ceremonies (called lubushtu in Akkadian). Aside from several pieces of jewellery, the statue was most likely adorned with a (horned) crown, a typical marker of divinity in Mesopotamia. Other paraphernalia include divine attributes and cylinder seals. Remarkably, shoes are not attested, perhaps because the gods were always carried.

The appearance of the cult image furthermore bore some divinatory significance. One list of omens, for example, is concerned with the statue’s position, the visibility of its face, its colour (red is positive; black, white and green are negative) and its radiance. If any of these things was not as it should be, disaster would descent on the land in the form of war, conquest by enemies and death of the king.

Making a god: the mīs pî ritual

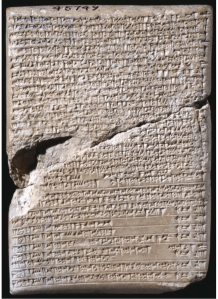

The Babylonian ritual text (BM 45749)

Now, the ancient Mesopotamians were confronted with an essential paradox: on the one hand, the cult statue was an object made by human hands and in need of regular attendance, but on the other, it was the god himself, unapproachable by simple humans and of a divine purity. How did it work when a new statue needed to be made or an existing statue needed to be refurbished? In that case, there was a specific ritual that allowed to work around this apparent dichotomy: the so-called ritual of mīs pî or “Mouthwashing”. Different versions of this ritual have been preserved, stemming from Nineveh and Babylon respectively. In essence, they come down to the same thing, nonetheless.

The goal of the mīs pî ritual was to efface all traces of human activity so that the statue became as pure and untouched as a god should be. This is achieved through both ritual acts and the recitation of incantations. The ritual starts at the moment when the repairs or creation of the divine statue are finished and it is ready to be (re)introduced in the temple. After some minor rites, the first incantation “Born in heaven by your own power” is recited and a first mouthwashing is performed. What exactly “mouthwashing” consisted of, is unclear, since the texts simply mention the term without elaborating on its meaning. Then the statue is taken to the riverbank, where an offering is made to Ea, god of sweet waters: a sheep is cut open and several tools, such as an axe and a chisel, are put inside it and it is thrown into the river. The significance of this rite lies in the fact that Ea is also the god of craft and craftsmen, and returning the tools to him is a first step of cleansing. Afterwards, the newly created god spends the night in a reed hut and sacrifices are brought to the great gods, the deities of purification, and the stars and planets: all the powers are invoked to help the process and to accept the new statue as one of their own. On the second day, more offerings and incantations take place, and the god is introduced into his cella in the temple, where the final mouthwashing is performed. At the end of the ritual, the god receives his first meal, indicating that the process of removing all human traces to render him divine is complete.

“The gods Ea and Asalluhi, by their exalted wisdom, opened their mouths with the ‘washing of the mouth’ and the ‘opening of the mouth’ and had them dwell on their pure pedestals in their lofty cellas for all time!” (inscription of Esarhaddon)

Bibliography

- Sollberger, Edmond (1974) “The White Obelisk.” Iraq 36 1/2, 231-238.

- Foster, Benjamin (2005) Before the Muses. Bethesda.

- Walker, Christopher & Dick, Michael (2001) The Induction of the Cult Image in Ancient Mesopotamia. Helsinki.

- Berlejung, Angelika (1998) Die Theologie der Bilder. Göttingen.

- Sallaberger, Walther (2000) “Das Erscheinen Marduks als Vorzeichen.” ZA 90, 227-262.

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike