Even though we have thousands of cuneiform texts, it is sometimes very hard to shape an image of the country and civilization that we are dealing with. Since the start of the Gulf war in 1990, excavations in Iraq have come to a virtual standstill, and only very few Assyriologists have been lucky enough to see the actual sites of the places which we encounter in so many texts. Luckily for us then, the textual material is so rich that it can make up for the lack of archaeological evidence. In the case of Babylon, the layout of the city can be virtually reconstructed with what we know today. Our sources can be divided into three main categories: the archaeological evidence, works of classical authors, and cuneiform texts.

Archaeology

The site of Babylon was systematically excavated for the first time in 1850, when Austen Henry Layard took some time off from his proceedings in the north of Mesopotamia and came down south to Babylon. Before him, several people had visited and rummaged the remains of Babylon a little, but with Layard systematic excavations began. It must however be said that those excavations cannot be considered proper scientific undertakings, and they are often rather seen as “organized plunderings”. All the objects of interest were dug up, put in boxes and shipped to the big museums of Europe: the Louvre, British Museum, and others.

Important archaeologists at Babylon: FLTR Layard, Fresnel, Van Lycklama à Nijeholt, Rassam

It was the German Robert Koldewey who introduced scientific excavation techniques at Babylon, and the largest part of what we know today stems from his work between 1899 and 1917. From that moment on until the end of World War II, the site of Babylon was abandonned. Only at the end of the 1950’s diggins were resumed by the Iraqi governement, in collaboration with German and Italian universities. All excavations stopped in 1990 when the threat of war became too pendant.

Classical authors

It lies in a great plain, and is in shape a square, each side fifteen miles in length; thus sixty miles make the complete circuit of the city. Such is the size of the city of Babylon; and it was planned like no other city of which we know. (Herodotos, Histories I.178.2)

Textual sources can aid to fill in the gaps that are left by archaeology: some Greek and Roman authors have written about the city of Babylon and its topography. A recurrent theme is the magnificence of Babylon’s city walls, the measurements of which are greatly exaggerated to create an image of Babylon as an enormous stronghold. Below you can find a table summarizing the ridiculous numbers given by the classical writers (at its largest size under king Nebuchadnezzar II the surface enclosed by Babylon’s outer wall was 900 hectares).

| author | perimeter in km | perimeter in stadia |

| Herodotos | 88,8 | 480 |

| Ctesias | 63 | 360 |

| Strabo | 71,2 | 385 |

| Curtius Rufus | 67,5 | 365 |

| Flavius Philostratus | 88,8 | 480 |

Cuneiform sources

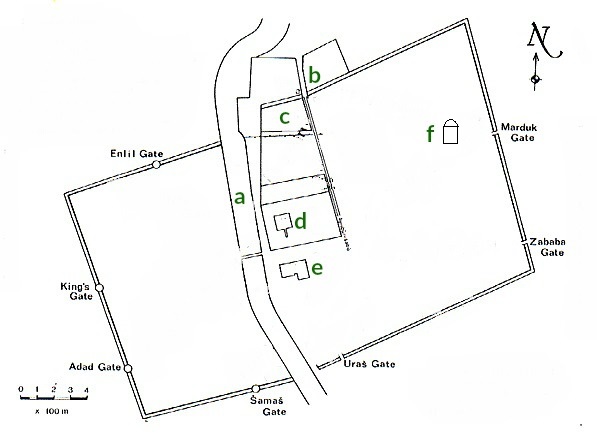

Because the classical works are not very reliable when it comes to Babylon, we must turn to cuneiform texts for veritable information, for example building inscriptions and historical reports. The most important cuneiform source is a list of topographical names called TIN.TIR = Babili. It is in fact a document listing temples and shrines dedicated to Babylon’s main god Marduk, but to us the appendix is much more interesting since it provides information about all kinds of geographical elements, such as walls, gates, rivers, canals, and neighborhoods. The text formed the basis for the virtual reconstruction of Babylon made by Andrew George. The map as presented here is not to be seen as a fixed image of the city, because it contains features dating from the seventh century BC to the second century AD. The highlights are explained below.

a Euphrates; b Ishtar gate; c Southern Fortress; d Ziggurat; e Esagila; f Greek theatre

Over time, the course of the Euphrates (a) shifted westwards, making it almost impossible to excavate the area west of the river as seen on the map. The river was of vital importance to Babylon: not only was it a commercial route, but it played a crucial role in cultic activities as well.

source: http://www.kadingirra.com/gates.html

The Ishtar Gate (b) is one of the most famous relics of Mesopotamia’s past. Today it can be seen in its fully reconstructed, glorious form at the Pergamonmuseum in Berlin; on the original spot in Babylon itself a replica was built. The gate was the city’s outer post on the processional way, which led from the main temple Esagila to the New Year’s house outside the city walls.

The Southern Fortress ( c) was the main part of Babylon’s citadel constructed by king Nebuchadnezzar, and was centered around 5 large courtyards. Its counterpart was the Northern palace (also called Hauptburg) just outside the city walls, but that building remains for the most part unexcavated. It is thought that the Northern palace was the royal residence whereas the Southern Fortress was a state building reserved for official business.

source: http://www.kadingirra.com/etemenanki.html

The ziggurat of Babylon was called Etemenanki, “temple of the foundation of heaven and earth” (d). It was the temple tower of Esagila (e), the main temple of the city dedicated to Marduk, the city god. It must have been a huge building visible from far away, but unfortunately nothing of it remains today except for its outlines.

The last structure indicated on the map is the Greek theatre which was built in the hellenistic period (from the end of the fourth century on). Though the existence of a Greek theatre at Babylon might seem surprising to non-Assyriologists, it was not to experts of the field, since the presence of a Greek community at Babylon is attested in cuneiform sources. Most probably, the theatre was the centre of Greek social life in Babylon during the last centuries BC. It continued to be used in the Parthian age and was even rebuilt in the second century AD. The Babylonian designation for “theatre” is bit tamarti, which literally means “house of watching”, as does the word “theatre” itself.

But what about the title of this post? The word “Babylon” could be written in cuneiform in many different ways. One of them is KÁ.DINGIR.RA, which was read in Babylonian as bab ili and means as much as “gate of the gods”; its phonetic resemblance to “Babylon” is obvious. Nonetheless it is quite improbable that the city’s name actually stemmed from that folk etymology, how befitting it might be.

Further reading

- Andrew George, Babylonian Topographical Texts, Peeters 1992

- Tom Boiy, De echte stad en de mythe, Davidsfonds 2010

- Colin Mc Evedy, Cities of the Classical World: an Atlas and Gazetteer of 120 Centres of Ancient Civilization (Babylon page 60ff.) , Allen Lane 2011

- http://www.kadingirra.com/introduction.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1Hbht4iNQg

What’s up, this weekend is good for me, since this

moment i am reading this enormous informative piece of writing here at my house.

LikeLike