The decipherment of the cuneiform script followed a long process. As you might remember from my first post, the cuneiform script was used to write different languages. In some cases, it was simplified to such a degree that it became an alphabet, which is a good thing for us: because of those simplifications we were able to decipher the writing system.

The term “cuneiform” (cuneiformis) was coined by Thomas Hyde (1700), but it was used alongside Kämpfer’s litterae cuneatae (1712). From 1818 on the word was officially part of the English language.

The very first cuneiform language that was deciphered was Old Persian, found in inscriptions of Persepolis. It was Pietro della Valle (1621) who was the first to write about the “remarkable inscriptions” found at Persepolis. Some decennia later, people started copying the texts they found. Worth mentioning are Jean Chardin and Carsten Niebuhr. Still it remained difficult to read the texts, but in 1802 Friedrich Grotefend was able to read short sentences such as “Darius, great king, king of kings, son of Hystaspes”.

The first big breakthrough came when researchers started to concentrate on the Behistun Inscription, a rock inscription found in modern Hamadan (West-Iran). Contrary to most inscriptions found in Persepolis, this was a very long text, which thus held a lot of potential for its decipherment. It had been known for a long time: the Frenchman Otter mentions it in his travel account (1734); its earliest attestation however can be found in Diodorus Sicilus who – wrongly – attributes the inscription to Semiramis.

The first big breakthrough came when researchers started to concentrate on the Behistun Inscription, a rock inscription found in modern Hamadan (West-Iran). Contrary to most inscriptions found in Persepolis, this was a very long text, which thus held a lot of potential for its decipherment. It had been known for a long time: the Frenchman Otter mentions it in his travel account (1734); its earliest attestation however can be found in Diodorus Sicilus who – wrongly – attributes the inscription to Semiramis.

The Bagistanus mountain is sacred to Zeus and on the side facing the park has sheer cliffs which rise to a height of seventeen stades. The lowest part of these she smoothed off and engraved thereon a likeness of herself with a hundred spearmen at her side. And she also put this inscription on the cliff in Syrian letters: “Semiramis, with the pack-saddles of the beasts of burden in her army, built up a mound from the plain and thereby climbed this precipice, even to this very ridge.” (Diodorus Sicilus, Library of History II.13.2)

It was Sir Henry Rawlinson who between 1935 and 1839 copied the inscription and started deciphering it. The enterprise was very dangerous: because all ladders available were too short, Rawlinson was lowered in a basket from the top. In the end, he succeeded and sent his copy to the Royal Asiatic Society in London, where it was published in 1849.

It was Sir Henry Rawlinson who between 1935 and 1839 copied the inscription and started deciphering it. The enterprise was very dangerous: because all ladders available were too short, Rawlinson was lowered in a basket from the top. In the end, he succeeded and sent his copy to the Royal Asiatic Society in London, where it was published in 1849.

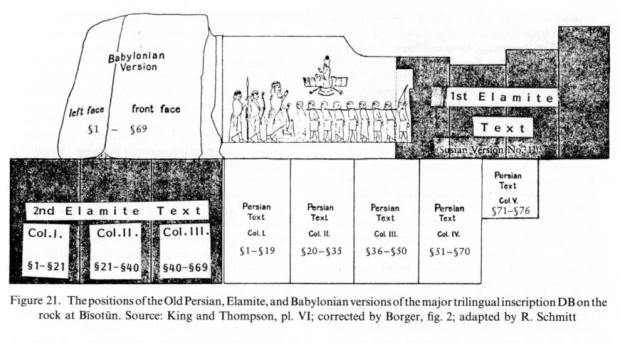

The inscription – so was discovered – contained a text in three different languages which were all written with cuneiform signs. The Old Persian text was deciphered first, because of its being an alphabet and the progress yet made by other researchers. Rawlinson succeeded in reading the full text.

The other two languages, as we know today, are Babylonian and Elamite. The Babylonian text was much more difficult to read than the Old Persian one. It was only with the help of newly found texts in Assyria that the following things became clear: the script was syllabic (Hincks), it represented a Semitic language (De Saulcy), the signs were polyphoneous and/or ideographic (Rawlinson), and a set of at least 642 signs was used (Botta). Elamite is still today a fairly unknown language.

The other two languages, as we know today, are Babylonian and Elamite. The Babylonian text was much more difficult to read than the Old Persian one. It was only with the help of newly found texts in Assyria that the following things became clear: the script was syllabic (Hincks), it represented a Semitic language (De Saulcy), the signs were polyphoneous and/or ideographic (Rawlinson), and a set of at least 642 signs was used (Botta). Elamite is still today a fairly unknown language.

The decipherment of Old Persian and the growing corpus of cuneiform texts boosted the knowledge of the Babylonian writing system and language, resulting in the translation of the Black Obelisk of Shalmanasser III by Rawlinson in 1850. When several different scholars claimed that they were able to read the cuneiform signs, the Royal Asiatic Society was a bit sceptical and put them to the test: Henry Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, William Talbot and Jules Oppert each received the same amount of ca. 800(!) lines of cuneiform writing to transcribe and translate independently from one another. On May 25th 1857 the different versions were reveiled, compared, and found similar enough to proof that they were based on “scientific principles”. The cuneiform script as it was used for Babylonian and Assyrian (both dialects of Akkadian) was officially deciphered!

The decipherment of Old Persian and the growing corpus of cuneiform texts boosted the knowledge of the Babylonian writing system and language, resulting in the translation of the Black Obelisk of Shalmanasser III by Rawlinson in 1850. When several different scholars claimed that they were able to read the cuneiform signs, the Royal Asiatic Society was a bit sceptical and put them to the test: Henry Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, William Talbot and Jules Oppert each received the same amount of ca. 800(!) lines of cuneiform writing to transcribe and translate independently from one another. On May 25th 1857 the different versions were reveiled, compared, and found similar enough to proof that they were based on “scientific principles”. The cuneiform script as it was used for Babylonian and Assyrian (both dialects of Akkadian) was officially deciphered!

And they lived happily ever after? Not for long: in 1850 Hincks realised that another language was written with cuneiform signs, for he was unable to detect semitic roots in his transcriptions. Based on the common title “King of Sumer and Akkad”, Jules Oppert suggested to name the new language Sumerian as opposed to the known Akkadian. To the present day our understanding of the Sumerian language is not as full as of Akkadian. However, I cannot thank the first Assyriologists enough for enabling us to read the 954 cuneiform signs collected this far.

Further reading

- Handcock, Percy, Mesopotamian Archaeology. London, McMillan, 1912.

- Budge, Wallis. The Rise and Progress of Assyriology. London, 1925.

- http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=the_decipherment_of_cuneiform

- http://www.livius.org/articles/place/behistun/

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rawlinson-ii

2 thoughts on ““In a clear and unmistakable light”: deciphering cuneiform”